“You start out making the game you wanna make and then you take away everything that isn’t fun. That’s how you make a fun game.”

Mark Long, CEO of the studio behind AAA blockchain first-person shooter Shrapnel, is someone I immediately get.

Long is an experienced trans-media executive: he’s worked for HBO, Microsoft Xbox, owned and operated his own gaming studio, and been a major in the US Army.

Turns out he’s also profane, frank, approachable and cares passionately about games and gamers.

In the world of blockchain gaming, there’s no shortage of startups with more ambition than experience, and promises to remake the world are thick on the ground. Long avoids hyperbole in his account of what Neon (his studio) is doing with Shrapnel, an extraction FPS whose main blockchain integration revolves around map and skin creation. The aim is tightly focussed – there’s a single game mode – and, as you’ll see below, the blockchain elements sit further in the background than in many similar projects.

The backstory

The game story is straightforward: it’s 2044, there’s a massive uninhabitable zone banding the earth, regularly bombarded with meteors. Your job is to go into this lawless, violent area and come back with a chunk of valuable meteor.

The chunks are the key game resource and the driver of the economy. Interestingly, crafted items give no gameplay advantage, so wealth isn’t necessarily linked to prowess. This seems to correspond to an aspect of Long’s personality – a desire for fairness – but also makes sense in maximizing the onboarding of mainstream gamers.

“The number of blockchain players is really small … so we are going after regular players,” Long tells me on a call from Seattle.

“The way to do this is just simply make a free-to-play game that’s fun to play. And then as you accumulate NFTs and you get to a certain dollar value, we’ll just send push notifications: ‘Hey, if you would like to create a wallet, you can have these [NFTs] and you can do whatever you want with it.’”

“We’re open to experimenting with every way that blockchain can improve the player experience and not cramming blockchain down your throat, or trying to do these egregious play-to-earn grinds that are really just pyramid schemes.”

Shipping product

With the sharp focus comes a tight timetable: Neon will be showing the first playable version of Shrapnel “behind closed doors” at the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco in March 2023. The game will be revealed publicly at the Consensus blockchain conference in Texas at the end of April.

“Shortly after that we’ll release what we are calling multiplayer experimental, or MPX, from the Epic Games Store. The final version of the game, the open beta, will come in the fourth quarter 2024.”

Shrapnel is being developed quickly compared to other AAA first-person shooters because there is no single-player game. There will be one painstakingly crafted multiplayer map, the rest will be created by the community.

“You’ll be able to create your own content for the game, mint it, and then blockchain provides the seamless attribution back to you, so that we can share revenue to you for your creation.”

Long says about a third of his team is dedicated to the blockchain, the other two-thirds to the normal game elements.

But does it feel right?

“We are completely focused on what I know is the most important thing about an FPS: gun feel. I could tell you if I start playing a game and I pick up a gun [and play] for eight seconds, I’ll tell you right then if I’ll be playing two weeks from now. It’s always about gun feel, and then the combat experience. The frequency, tempo, character it takes.”

Long says Neon is showing the game community “how the sausage is made”, in terms of opening up the development process.

“This is radically different to how game developers normally work. [Normally] we go off and design and work in secret and only show the game at the very end when it’s completely ready and polished. So it’s against every instinct we have to be doing this.”

Community and worldbuilding entwined

Long points out that mainstream observers of crypto may be missing the role that fictional worldbuilding plays in communities.

“It’s community based, right? Which is the thing that people don’t see from the outside. So like ‘Why are these knuckleheads buying $5,000 monkey pictures?’ [People on the outside] don’t understand that on the inside it’s this vibrant community [built around] the art and then talks about all kinds of things, including building fiction around characters.”

As a game creator, filmmaker, and writer – Long has written a novel and several graphic novels – he believes character is both the foundation of worldbuilding and the key to creating a trans-media franchise.

“When we designed the world of Shrapnel, it’s all character-based. We built out over 60 major characters. That will give the writer that comes behind us and is commissioned to write a novel the flexibility to mix and match characters and how they interrelate.”

“If a franchise is successful, it really helps if you’ve systematically designed the fiction to be spread across media.”

Long is now planning a series of 6-10 minute films for Shrapnel with director Jerry O’Flaherty and Nathan Maddams (from Plastic Wax in Sydney). This team has already created a sharp 2:44 trailer that has received more than 100k views combined (see embed below). The cinematic shorts are made with the same technology being used to construct the game proper: Epic’s Unreal Engine 5.

“What we are going to do is take the level from the first multiplayer – it’s our virtual set.”

The purpose of the movies is to fill out the game world.

“In a multiplayer game, you just don’t have much opportunity to tell the story, but you watch these videos, I think when you go back and play again, you’re able to project your imagination into the real characters and real story.”

Making a blockchain gaming platform

Long uses Epic and the Unreal Engine as an example of another big ambition: to create an off-the-shelf blockchain platform for other game developers.

“There’s no soup to nuts solution for Web3 and gaming. You have to cobble it all together. We realized in doing that we were potentially building a platform that other developers could use.”

“So we have branded our platform Game Bridge, or simply Bridge, and we hope in the future – if Shrapnel is successful – to attract other developers onto our platform.”

“Most game developers, us included, just wanna make cool shit. I don’t wanna fuck around with trying to figure out if this is the right layer one or token economy, I would prefer somebody else to figure all that out.”

On the creative journey of gamers

Long describes a typical trajectory of young gamers going from Minecraft, to Roblox, then into Fortnite creator mode, and then hitting a wall of early adulthood where there isn’t a big creative gaming platform.

“I just think that players are ready after graduating from each one of these game platforms to tackle modding at an unprecedented level, at a professional level, using the same kinds of tools that we use, but I don’t think the learning curve is going to be so steep.”

Long sees AI having a revolutionary impact on creating virtual worlds and modding games. He uses generative models like Stable Diffusion that take text inputs and generate images as an example.

“These are stunning results. I think we’re going to see the same things with text-to-mesh, text-to-texture, text-to-level … you’re going to be able to give these models what you really want it to do without learning Blender and 3D modelling and importing high-level shader languages. That would be super dope.”

On the latest winter

Long has delayed Shrapnel’s token offering because of the current crypto downturn.

“I’ve been in blockchain since early 2016, so I’ve been through two of these winter cycles and you just have to have diamond hands, man. You can’t look at your wallet. You don’t lose any money if you don’t sell it.”

“Anyone who says this is the end of blockchain is high. But it’s pretty tough to watch. I have friends … doing blockchain gaming platforms who took a higher valuation, because the market was frothy, and now they regret that … it looks like they will have to go another year or two with the money they got and they won’t be able to raise another round because they priced themselves too expensive. Fortunately we didn’t do that because of my previous experience … don’t go crazy on your valuation.”

Where the passion began

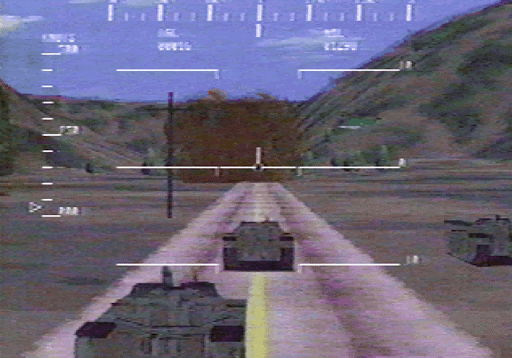

The commercial game that had the biggest influence on Long was Doom II – “I was blown away because of that sense of immersion” – but before that, his experience in the US Army was key to setting him on the path of creating games.

In the Army he worked on SIMNET, a “seminal networking and simulation project”.

“Up till then simulators were for pilots because they were usually expensive, like $40-70 million.”

“But as graphic compute power came down [in cost], it became possible to make a simulator for a tank crew. And then they networked those so they could play together in a virtual battle. And that led to me … playing war games professionally at a classified facility. It was nuts.”

“I got exposed to Silicon Graphics workstations and Sun workstations, and I read the words ‘virtual reality’ for the first time, and I decided right there, that’s what I wanna do. I wanna make virtual reality games. That was 1991.”

With partner Joanna Alexander, he designed a home virtual reality system, and then started a games studio (Zombie Studios).

“Our first three games were designed for head-mounted displays. And then of course, that didn’t fucking happen.”

The curse of the head-mounted display

Because of this experience, Long is fast and hard in his assessment of whether devices such as Meta’s Quest have a future.

“It’s just like the current generation, like nothing’s changed except that HMDs [head mounted displays] are perfect, and still it’s too isolating a social experience.”

“It’s cool, but it’s just not that cool … and people who are obsessed with it, like Mark Zuckerberg, are just chasing something that’s never going to happen. Ask anyone who owns a Quest when was the last time they used it. Like, a year ago.”

“It’s not going to be a thing. Virtual reality is going to be expressed in a different way: with large screen displays, face and gesture, voice recognition.”

“You don’t have to wear a HMD to do VR.”

The problem with NFTs

“I just hope that we are pointing regular players towards the idea of digital ownership and gaming. Players are up in arms against NFTs and blockchain for some really legit reasons. One: do not fry the fucking planet by mining your layer one. We’re using Avalanche because it’s carbon neutral.”

“Number two: it’s a lie that you can buy an NFT and take it to other games. They’re not interoperable and there’s no real business model that provides for that. So stop saying that, and stop telling people you can quit your job driving a taxi and earn money playing a video game.”

Long describes the situation in the past where players owned games as physical copies, and the value felt real. With the rise of free-to-play games the dynamic changed.

“Now 85% of purchases are in-app, but you never really own any of that … It’s definitely part of my inspiration to give ownership back to players.”

It’s clear that despite his many years in the industry, Long has an idealistic streak.

“With Shrapnel, we’re trying to make a game that people can make their own, I think is a really exciting idea. And I think if I left anything with the game industry at the end of my career, if we succeeded with that, that would make me super happy because I’d be sharing what I’m so passionate about and letting others enjoy that same joy.”

Mark Long’s passion and know-how are even clearer when you hear his voice. This discussion will feature in a Polemos Pharos podcast with prominent and fascinating people in the blockchain gaming world, to be launched end January 2023.

Note that the portrait image heading this article is AI-generated, based on Mark Long’s likeness (Polemos/MidJourney)