Sparkball is a team-based game that involves fighting and goal-scoring – a kind of cartoon battle-football – and like many previously self-described blockchain games, it’s running away as fast as it can from the “web3” label.

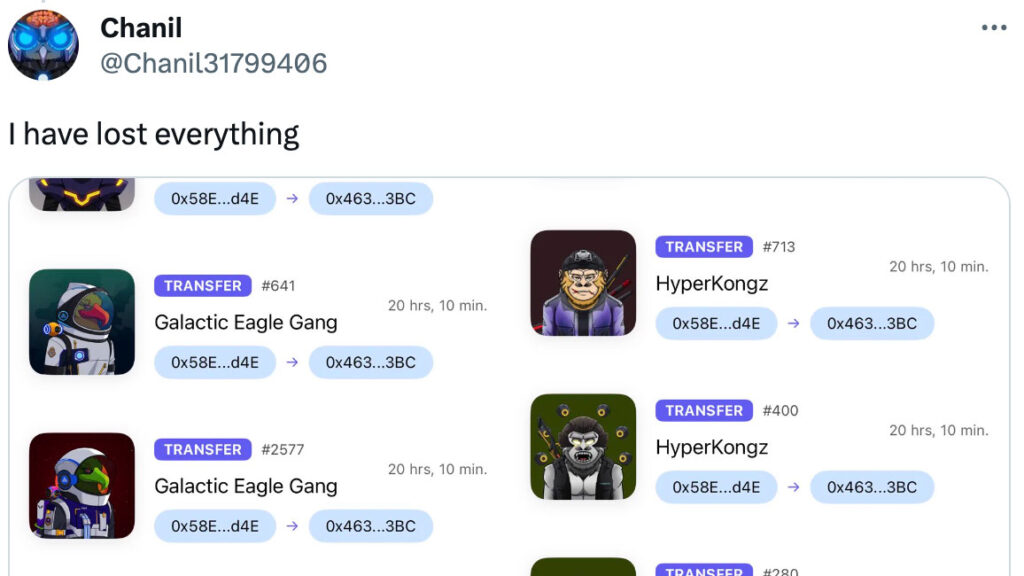

But it wasn’t fast enough to get away from the scammers. Last weekend Sparkball founder Chandler Thomlison’s Discord account was hacked and his game’s Discord server taken over.

The scammer playbook is to hack into a high-level admin account on a game Discord, often by getting the admin to click on a link, and then boot all the other admins so they can’t be stopped.

They then announce some bogus mint or giveaway, get the community to connect their wallets in the expectation of that event, and drain the wallets.

It’s a simple, socially engineered exploit that finds a single point of weakness at the top of an organisation and then trades on community trust to steal NFTs and crypto.

Discords are chat forums widely used in blockchain gaming – along with gaming in general – to communicate with communities.

Polemos fell victim to exactly the kind of attack used to breach Sparkball in June. In our case, the scammers hijacked an admin account below the very highest level, and therefore we were able to get back in control of the server without appealing to Discord’s management to intervene.

In the case of Sparkball, the scammers assumed total control, even running a script that picked up any time a community member used the words “scam” or “hack” to ban those comments.

This meant people could not warn each other of what was afoot.

I admit to a kind of fascination with the forensics of these attacks, the kind that has other people glued to true crime podcasts. The damage is real: in the case of Sparkball, some community members say they lost thousands of dollars worth of NFTs.

Thomlison only regained control of the server by getting the central Discord admins to reset the server and hand it back to him.

The episode draws out a few interesting lessons:

True community size

At Polemos, we track 37 promising blockchain games closely in something we call the “Game Review Dashboard”. It’s a spreadsheet that lists the games with their vital statistics: the blockchain they are on, their Discord community size, how many members of that community are active, their Twitter followings, the price of their NFTs and tokens (if any), and their release schedule. Because we update the numbers every week, we can see trends.

Sparkball is one of the 37 tracked games. Before it was hacked, the game had around 33k Discord followers, a middling number on our spreadsheet. Of those followers, around 1600 were active over a two-week period. This percentage (5%) is around half the average for our tracked games.

After the hack and the reset of the Sparkball server, the inactive Discord followers had all disappeared. The total community is now around the same size as the old active members (1600). In other words, the total number of people who have signed up for a game’s Discord is not worth paying attention to, and only the active Discord number is a useful measure of community size. We have removed total Discord members from our calculations of game size.

Another data point here is that the world of engaged blockchain gamers is quite small: the sum of all active Discord members in our list is 182k. This number is not de-duplicated, it includes a big chunk of the same people counted many times.

People are the softest target

Convincing a human to click on a link seems to be much easier than mounting a technical attack. I need to interview someone knowledgeable about this in order to bring you better insights here, but the combination of trust-based communities, single-hierarchy admins, and single-platform comms feels inherently risky.

Limits of decentralization

What happened when Thomlison lost control of his Discord undermines the practice of decentralization, if not the theory. He had to go to Discord management – presumably through email, telephone or some other old-school channel – and ask them to kick the bad guys out. Of course they complied, because in a world of multi-modal communication – the real world – it’s not so difficult to tell when the bad guys have staged a coup. They do bad things. They aren’t forthright about their identities. Nobody knows them.

In the case of Sparkball, the backstop for a hijacked community was a central authority. Crypto purists will tell you this isn’t necessary, and that the answer is more and truer decentralization. But I’m not sure I want to live in a world where there really is no one to call when the crooks have taken over.

Interview with Thomlison

As it happens, I recently interviewed the founder mentioned above, Chandler Thomlison, for the Key Characters podcast. Thomlison is a great talker and paints a vivid picture of how tough it has been making a game.

“I started Sparkball about seven years ago. I don’t come from gaming at all. I was a consultant, I just always wanted to make video games. As a kid [I decided] I’m gonna make video games at some point in my life. Finally I had enough money and spare time and said, ‘Hey, I’m gonna try this myself. How hard can it be?’”

Thomlison’s answer to that question, even before the Discord hack, was already “incredibly hard”. Now he’s got more tough experience to bank. Making games is a long, gruelling process. I aim to get that interview cut and published next week. To be transparent about interviews, I usually speak to my interviewees for 45-60 minutes and then cut the conversations down to 20-30 minutes. Everything is more interesting that way.

Please let me know – you can hit reply on this email – any other big personalities in gaming/crypto/tech you’d like to hear from.

The Wildfile is live

Back when I interviewed Paul Bettner and Katy Drake Bettner for Key Characters, they said a lot about blockchain tech without telling me exactly how they were going to incorporate it into their MOBA card game spectator sport Wildcard.

Now we know. The Wildfile is an NFT (unique digital asset) that records all a person’s Wildcard participation – attendance at matches, community events etc – while being bound to that person permanently.

Wildcard describes the Wildfile as “your own unique permanent record of your life in the Wildcard universe”. It’s free for people who already have a Wildpass NFT, and it can’t be traded. It also comes with a unique name, as in the screenshot above.

All this sounds a lot like a database entry. But then again, as BG sage Sam Peurifoy says, “a blockchain is fundamentally just a read/write public access database”.

Also, because this project is being run by the Bettners, it’s worth paying attention to. There is a sense of solidity there that is reflected in the detail. No one ever knows if a game is going to be a hit, but it seems that developers maximize their chances with experience and attention to detail. Watch “the best interview yet” with the Bettners.

Enjoy our reporting? Sign up for this Pharos newsletter and receive an update every week for free.